— 1. Introduction —

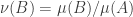

In the study of measurable dynamics, the basic object of study is a measure preserving system: a quadruple , where

is a set,

is a

-algebra over

,

is a probability measure on

and

is a measurable map such that, for each

, we have

, where

. If there exists a set

such that

and

, then we can consider the measure preserving system

, where

,

and

. This system is a piece of the original system

, and thus can be studied separately. If there is no such set

then we say that the system

is ergodic.

Analogous to the way primes are the building blocks of the integers, ergodic systems are the building blocks of measure preserving systems. When we want to prove certain statements about general measure preserving systems (such as Furstenberg’s multiple recurrence theorem, which is equivalent to the celebrated theorem of Szemeredi in arithmetic progressions) it might be useful to reduce them to the case when the system is ergodic. The tool that allows for this reduction is called the ergodic decomposition and can be compared to the fundamental theorem of arithmetic in our analogy between ergodic measure preserving systems and the prime numbers. I have used this method before on this blog, when presenting the ergodic theoretical proof of Roth’s theorem.

Before I state the theorem I need to establish some notation. Throughout this post, will usually denote a measurable space and

will be a

-measurable map. A probability

is invariant under

(or

-invariant) if for all

we have

, equivalently if

is a measure preserving system. The probability

is ergodic if for every

with

we have

or

, equivalently if the system

is ergodic.

Theorem 1 (Ergodic Decomposition) Let

be a compact metric space, let

be the Borel

-algebra and let

be

-measurable. Then there exists a map

that associates with every

a

-invariant

-ergodic probability measure

in

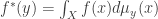

such that for every

-measurable function

, the map

is

-measurable and invariant under

and for every

-invariant probability

and every

we have

The conclusion can be informally stated as , i.e., any

-invariant probability is the convex combination of the ergodic measures

.

EDIT (on July 9th 2019): Theorem 1 follows from more general results of Farrell and Varadarajan; see Theorem 9.5 in this paper.

In this post I will discuss and eventually give a full proof of the following weaker version of Theorem 2, which is in practice often strong enough.

Theorem 2 (Ergodic Decomposition) Let

be a measure preserving system where

is a compact metric space,

is the Borel

-algebra and

is a Radon measure. Then for

-almost every

there exists a

-invariant, ergodic Radon probability measure

such that for every

, the map

is

-measurable and invariant under

and

For the proof of Theorem 2 I will use the technology of disintegration of measures. I posted about this topic recently, and all the background can be found on that post.

— 2. Alternative approach —

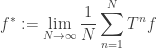

Before giving a rigorous proof of Theorem 2 I will briefly describe an alternative way to think about this theorem. This can be formalized to give a full proof of the ergodic decomposition theorem. Let be a compact metric space and let

be the Borel

-algebra. Let

be a map measurable with respect to

. Let

be the set of all

-invariant probability measures over

. To see that

is non-empty, let

be arbitrary and let

be the probability measure over

defined by

. Since the space of probability measures over

is weak

compact, there exists some weak

limit point

for the sequence

and it is not hard to see that

.

Observe that is a convex set. In other words, if

and

then

. Recall that an extreme point of a set

in a linear space is a point

such that whenever

is written as a convex combination

of points

in

and

, then

.

Proposition 3 A measure

is an extreme point of the set

if and only if

is

-ergodic.

Proof: First let be an extreme point. Let

be an invariant set such that

(so we want to show that

). Let

be the probability measure defined by

for any

. Since

and

is invariant under

we have

Hence . If

, then

and

is also

-invariant. Thus we can create a

-invariant measure

defined by

and we have

. Since

is an extreme point in

this can’t happen, and hence

as desired.

Now we prove the converse. Let be ergodic, and write

with

. For any

-invariant set

we have

Since and

(strict inequalities!) we deduce that

. This implies that both

and

are ergodic measures.

Now let be arbitrary. By the pointwise ergodic theorem there exists a set

such that

and for each

we have

By the previous remark, also , and hence, again by the ergodic theorem, we have that for

-almost every point

in

we have

Since the right hand side of the two previous displays is the same, we conclude that . Since

was arbitrary, we conclude that

, and then it follows that

as well. Therefore

is an extreme point in

.

Denote by the subset of

-ergodic measures. We now recall Choquet’s theorem, which, in this case, says that for any

there exists some measure

on

(yes, this is a measure on a space whose points are measures!) such that

. Note that this equality is between measures of

, it can be made more precise by

for every

.

This conclusion follows the same spirit as Theorem 2 and is also called the Ergodic Decomposition. For most (if not all) applications, this is enough, although we get maybe a better understanding from the statement and proof of Theorem 2.

— 3. Examples —

I will try to give some intuition about Theorem 2 by exploring some examples first.

Example 1 Let

be given the discrete topology and let

be the uniform measure (more precisely,

). Let

,

and

. The set

is invariant under

and

, hence the system

is not ergodic.

However, if we restrict

to

and renormalize it, we obtain a probability measure which makes the system ergodic. More precisely, let

and

. Then

is and ergodic measure, in other words, the system

is ergodic.

Also, if

is the point mass at

(so that

and

), then the system

is also ergodic (one can also think of

as the normalized restriction of

to the invariant set

).

Finally, observe that we can write

as the convex combination

of the ergodic measures

and

. If we let

, then we can write informaly

.

Example 2 Let

be the torus group and let

be the unit square with the usual topology and the Borel

-algebra. Let

be the Lebesgue measure on

and let

where

is some irrational number. Any set of the form

, where

is a Borel set, is invariant under

. Therefore the measure preserving system

is not ergodic.

To try to mimic the previous example, we can take some Borel set

such that

, and let

. The probability

is

-invariant but, unlike in the first example,

is not ergodic (for any choice of

).

Regardless, it is still quite intuitive what we need to do. Let

denote the (one dimensional) Lebesgue measure on

. For each

, let

be the measure defined as

. It is not hard to see that

is

-invariant and ergodic (it is a not completely trivial exercise to verify that it is ergodic. One can show this, for instance, using Fourier analysis). Moreover it follows from Fubini’s theorem that

for any

. To make this decomposition compatible with the notation of Theorem 2, let

for all

. Observe that the function

does not depend on

. Thus, applying Fubini’s theorem again we have

Example 3 Let again

with the usual topology and let

be the Lebesgue measure. Let

. Again, any set of the form

, where

is a Borel set, is invariant under

and hence the measure preserving system

is not ergodic.

However, unlike the previous example, not all the

-invariant measures

(defined by

) are ergodic. Indeed, the set

is invariant under

but

. This shows that the measure

is not ergodic.

In fact the measures

are ergodic exactly when

is irrational (again, this can be proved with some Fourier analysis). Since the set of irrational

have full measure on

, the ergodic decomposition of

is the same as the one on the previous example, using only the irrational values for

.

However, in this example there are more ergodic measures. Indeed let

be some rational point and let

be arbitrary. Denote

by

. Then the probability measure

defined by

is

-ergodic. We have now found all ergodic measures for this system, so any

-invariant measure

can be decomposed as

for every

.

— 4. Proof of Theorem 2 —

Example 3 hints that in order to find all the ergodic measures of a given system, one should look at the invariant sets (observe, however, that not all -invariant sets give an ergodic measure: the set

is invariant for the system of Example 3 and yet no ergodic measure has

as its support).

Proposition 4 Let

be a probability preserving system and let

Then

is a

-algebra.

Proof: Let and let

. Then

and hence is closed under complements. Now let

be a sequence of sets in

and let

. Then

and hence is closed under countable unions and therefore it is a

-algebra.

Henceforth we will call the

-algebra of invariant sets. It turns out that the ergodic measures that appear in Theorem 2 are the measures that arise from the disintegration of

with respect to the

-algebra of invariant sets.

Lemma 5 Under the conditions of Theorem 2, let

be a

-subalgebra and let

be the disintegration of

with respect to

. Then for every

there exists a set of full measure set

such that for every

we have

Proof: Let . For

and let

. Then

is

-measurable and hence

for -a.e.

.

Lemma 6 For

-a.e.

, the measure

that arises from the disintegration of a

-invariant measure

with respect to the invariant

-algebra

is

-invariant and ergodic.

Proof: We first prove that for almost every ,

is

-invariant. More precisely, we will find a set

with

such that for every

, the measure

is

-invariant. Let

be a countable dense set. It suffices to show that for each

there exists a set

with

and such that for every

we have

. Recall by the construction of conditional measure that

, so we need to show that

-a.e. But this follows from the following computation, which holds for each

We now show that almost every is ergodic. It suffices to show that for every

, there exists a set

with

and such that for every

,

The pointwise ergodic theorem (see Theorem 2 in this post, or more precisely this stronger version) implies that the left hand side equals for every

in a full

-measure set. On the other hand, the left hand side is

(where the conditional expectations are both taken with respect to the measure

). The desired conclusion now follows from Lemma 5.

Proof: } Let denote the invariant

-algebra and let

be the disintegration of

with respect to

, for some

with

. By Lemma 6 each of the measures

is

-invariant and

-ergodic. By the properties of the disintegration of measures we have that for every

, the map

is

-measurable, and hence it is

-measurable and

-invariant. Moreover, it follows from the properties of the disintegration of measures that

and this finishes the proof.

Pingback: Disintegration of measures | I Can't Believe It's Not Random!

Is constant over every set in

constant over every set in  ?

?

sorry couldn’t get latex code to show up properly …

Also, in the statement of the theorem, wouldn’t a measure have to be assigned to a set, and not an element y of ?

?

The measure is not constant. Given a set

is not constant. Given a set  , by definition we have

, by definition we have  .

. a measure

a measure  , but each of the measures

, but each of the measures  is itself a function from

is itself a function from  to

to ![[0,1]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5B0%2C1%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) .

.

Regarding the theorem, it assigns to each point

I like the present reasoning that the conditional probabilities are ergodic. I know related statements from the Maitra paper. There are proofs of this using the ergodic theorem, see e.g. the lecture notes by Omri Sarig. I always feel lost reading that proof. ( I think because the several integration variables do not appear.) Do you know that proof? Can you make it more precise? I would appreciate to understand it.

Dear mOe, thanks for your comment!

I am not familiar with Maitra’s paper. If by Omri’s notes you mean http://www.math.psu.edu/sarig/506/ErgodicNotes.pdf (it’s Theorem 2.5 there) then the proof has indeed a different flavor.

The idea is to use the ergodic theorem which implies that is the conditional expectation of

is the conditional expectation of  in

in  . In other words,

. In other words,  for almost every

for almost every  .

. , if this equality holds for every

, if this equality holds for every  (assuming wlog that

(assuming wlog that  is compact) then

is compact) then  is indeed an ergodic measure.

is indeed an ergodic measure. one obtains a full measure set of

one obtains a full measure set of  ‘s in

‘s in  for which

for which  is ergodic.

is ergodic.

For any given

In fact it suffices to check it for a dense subset of functions, and taking a countable dense subset of

I’m actually a little confused by your proof of ergodicity of the mu_y’s. Isn’t there an order of quantifiers issue here? You’re proving that for every I, you have mu_y(I)=0,1 for almost every y. But you want to show that for almost every y, you have mu_y(I) =0,1 for every I. If the sigma algebra I was countably generated, you could exchange the order, but I’m guessing that in the generic situation it is not countably generated, e.g. if T is an irrational rotation of the circle. Thoughts?

That is indeed an interesting subtlety which I had not consider, I am afraid you are right in that one needs the -algebra

-algebra  to be countably generated which is not always the case. The simplest way I see of avoiding this issue is by removing from the whole space

to be countably generated which is not always the case. The simplest way I see of avoiding this issue is by removing from the whole space  a set of measure

a set of measure  (the measure is

(the measure is  here) so that

here) so that  becomes countably generated.

becomes countably generated.![[0,1]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5B0%2C1%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002) with the Borel

with the Borel  -algebra and Lebesgue measure (for a quite nice and precise description of this theorem, see Vaughn Climenhaga’s nice posts https://vaughnclimenhaga.wordpress.com/2015/10/22/lebesgue-probability-spaces-part-i/)

-algebra and Lebesgue measure (for a quite nice and precise description of this theorem, see Vaughn Climenhaga’s nice posts https://vaughnclimenhaga.wordpress.com/2015/10/22/lebesgue-probability-spaces-part-i/)

That one can remove such a set follows from the classical fact that any “reasonable” measure space is isomorphic to

Interesting. How does it follow that you can find such a set? I don’t see how the fact that X is standard helps — I’m not sure how to do it for an irrational rotation on the circle, actually.

Sorry, what I said did not make complete sense. What I had in mind is to identify the -algebra

-algebra  with an equivalent countably generated

with an equivalent countably generated  -algebra

-algebra  (equivalent in the sense that for any

(equivalent in the sense that for any  there exists

there exists  such that

such that  ).

). is infinite (and actually each point

is infinite (and actually each point  belongs to some set

belongs to some set  with

with  measure) it is equivalent to the trivial

measure) it is equivalent to the trivial  -algebra

-algebra  .

.

For the case of an irrational rotation (which is already ergodic), while

I agree, you can prove you can’t do the other thing for the irrational rotation. I’m still a little confused, though. Don’t you still need to say at some point that for a.e. y,

nu_y(I)=nu_y(tilde I) for all pairs I and tilde I as you describe?

You know that the mu measure of the symmetric difference is zero, but that only tells you that the nu_y measure of the symmetric difference is zero for almost every y, which gives you the same quantifier problem, no?

(Thanks for thinking about this with me. I’m trying to write down an ergodic decomposition theorem in a setting where I don’t have easy access to an ergodic theorem, so am trying to avoid it.)

The way I’m thinking, one replaces with

with  at the beginning of the argument, and take the disintegration with respect to the (countably generated)

at the beginning of the argument, and take the disintegration with respect to the (countably generated)  , so there is no need to worry about how

, so there is no need to worry about how  and

and  differ with respect to the disintegration measures

differ with respect to the disintegration measures  .

.

Well, you still have to show that those measures are ergodic, though, which is a statement about I, not tilde I.

You are right, the invariant sets are still the ones in regardless.

regardless.

I thought a bit more about this issue, and I think it is possible to fix the proof by proving ergodicity instead by studying invariant continuous functions (the idea being that there is a countable dense subset of continuous functions), but it will take me a while to write down all the details (assuming this works at all).

Pingback: Polygonal billiards | Bahçemizi Yetiştermeliyiz

I don’t see why the final set $Y$ measurable since it is a possibly uncountable union of the $Y_\mu$. Perhaps you just meant to highlight that the measures $\nu_y$ don’t depend on $\mu$, only on $T$? In the statement of theorem 1 though, it seems that $\mu$ is just some fixed measure and in that case doesn’t it suffices to just take $Y=Y_\mu$?

You are right, one needs to pass to the completion of the Borel -algebra (with respect to

-algebra (with respect to  ) in order for

) in order for  to be measurable. The idea is indeed that one has the ergodic measures

to be measurable. The idea is indeed that one has the ergodic measures  independent of the measure

independent of the measure  . Of course one can obtain a weaker version of Theorem 1 where one starts with a fixed measure

. Of course one can obtain a weaker version of Theorem 1 where one starts with a fixed measure  to begin with, and then one only needs the set

to begin with, and then one only needs the set  (which is measurable with respect to the Borel

(which is measurable with respect to the Borel  -algebra). For this weaker version there is also no need for Lemma 5.

-algebra). For this weaker version there is also no need for Lemma 5.

In example 2, wouldn’t it be more proper to call the group T the circle group, and denote it S? And then X=T^2 would be the torus.

It boils down to a choice of notation and terminology. Personally I think of as the

as the  -dimensional torus, including for

-dimensional torus, including for  .

. for the additive group

for the additive group  and

and  for the multiplicative group of complex numbers with absolute value 1 (of course these groups are isometrically isomorphic but it helps to distinguish additive and multiplicative notation)

for the multiplicative group of complex numbers with absolute value 1 (of course these groups are isometrically isomorphic but it helps to distinguish additive and multiplicative notation)

Also I tend to use the symbol

Pingback: Three different entropies, variational principle and the degree formula. – Blog Tigle goes here

Pingback: Inaugural post: Three different entropies, variational principle and the degree formula. – That Can't Be Right